By Nathan Thornburgh in Roads & Kingdoms

The brain trust at the Economist Intelligence Unit regularly lists Port Moresby, the capital city of Papua New Guinea, as one of the world’s least liveable cities. Among their complaints: post-colonial malaise, poor schools, and, of course, lots of crime.

That’s where the Raskols come in. These urban gangsters are both the tormentors and occasional protectors of the settlements they live in. The settlements, little more than shantytowns, are divided along ethnic lines, and tribal conflict has been a way of Papua New Guinea life since long before the Australian colonists ever arrived. Raskols protect their own when violence strikes. But outside of those moments of need, they also steal, rape and murder.

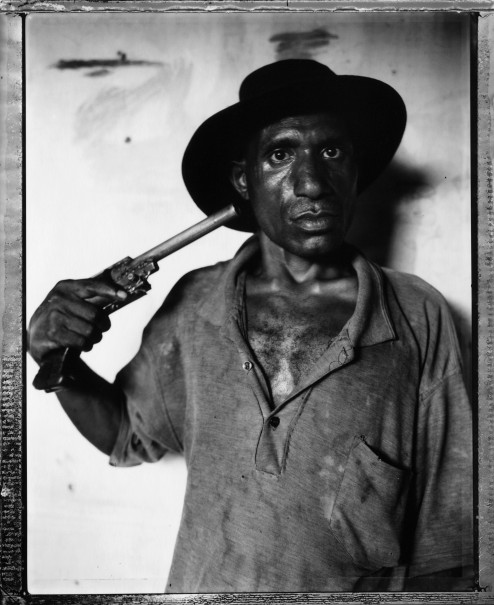

The fact that Raskols and their curious uniform—handmade firearms, aviator shades and highlander talismans—have gained notoriety far outside of Papua New Guinea is largely due to the work of documentarians like Australian photographer Stephen Dupont. His book Raskols, full of searing portraits like the ones above, gives readers a glimpse into the personalities of these enforcers, but it also, in the eyes of some, glorifies a very real and very predatory subculture. Yesterday we caught up with Dupont, who has just arrived home in Australia after an assignment in Afghanistan, about Raskols, his critics, and why Port Moresby isn’t as bad as the Economist thinks.

Roads & Kingdoms: How was Kabul?

Stephen Dupont: Same same, but different. I guess they’re all gearing up to leave. There’s a vibe that people have had enough and just want to get out. Certainly with the Australians, who I was with.

R&K: You’ve mentioned in interviews that you don’t see Port Moresby as being as bad as cities like Kabul.

SD: Port Moresby gets an unneccesarily negative rap… Certainly when I first went there in 2004, it was pretty grim. But I’ve been in some cities in Africa that were far more dangerous and far more unliveable than Port Moresby. It’s improving. The fact that there’s a big mining boom has helped. They’ve got a big cinema and some shopping complexes coming up.

Yes, Raskols [are] still running around the city and doing what criminals do, robbing and raping and nasty things like that. But I think again, it’s not Kabul, it’s not Aleppo. It’s not what Grozny used to be, not Lagos, or even parts of Johannesburg or Zimbabwe. There are certainly parts of the world that I would feel more scared as a white person.

That’s also because I’ve been going there for a while. It’s still a city with razor wire, compounds, and people do tend to hide behind their gates. But embassies are running, business is running, expats are driving everywhere.

R&K: How many trips have you made out to Port Moresby?

SD: Probably about 12 trips. My 2011 fellowship [at Harvard's Peabody Museum] allowed me to spend a lot of time there working on my next book. It doesn’t look at Raskols so much. The underlying theme is to look at decolonization, how New Guinea is changing rapidly. I was really focusing on tribal traditions.

R&K: Are there aspects of a tribal culture to the Raskols? Or is it the same kind of gangsterism you’ll find anywhere else?

SD: It really is quite tribal. And territorial. The settlements are like ghettos. These gangs rise up to really act as a security force to protect the settlements in times of tribal conflict. But individuals will often go off on their own and commit crimes.

On the main roads at nighttime they’ll often try to jack cars, basically armed holdup stuff… particularly Friday and Saturday night when they’ve been around alcohol or drugs.

Their culture really comes through in the way they dress and behave. They have tribal colors. But you’ll see a little bit of western culture. Ice Cube and Bob Marley t-shirts with a traditional Billum bag [a lot will wear billums around their neck].

And something I don’t think you’ll see in another part of the world, is that they make their own guns. I think it’s quite strange, and beautiful, almost like art pieces… It sort of goes back to how they would make their weapons in tribal times.

R&K: What do you say to critics who say the work just “glorifies” gang culture?

SD: There’s always a risk in the representation of any gang or military culture where you’re showing people with weapons and so forth. But that aside, it’s more about: this is reality. This is how they are. My job as documentary photographer is to represent them as they are, not to glorify them. When I made the photograph, I didn’t set them up. I would go so far as to ask someone to stand in front of the camera, but then I would just wait, to capture something that revealed something.

Within their gang culture, they are vain, they are egotistical, they want to show off their guns. That’s just who they are. The only answer then would be to not show them, but that’s not who I am.

Sebastião Salgado gets criticized for romanticizing the poor, the refugees. It comes down to this: if you’re a photographer, you’ve got to present it in the most creative way possible… His photography is stunningly beautiful. He just chooses to photograph that subject matter.

It’s not Hollywood, we’re not doing a fashion show here. We’re trying to capture a side of society that just happens to be a dark side.

R&K: The Raskols are mostly young men of the same age as the troops you photographed in Afghanistan. Did you see any similarities in them as young men?

SD: Be it a gang in Port Moresby or a platoon in Afghanistan, there’s that sense of family, of camaraderie. Raskols stick together. And they definitely use a form of uniform. Certainly, though, soldiers are there to perform a job their government has endorsed. You can’t really compare soldiers to criminals.

R&K:How do the tribal elders feel about the presence of the Raskols?

SD: Generally speaking, the elders are against Raskol culture. I’m actually dealing right now with that kind of situation: I’m doing a documentary about a rugby league, and one of the coach’s sons was one of the Raskols I photographed.

The son was shot and killed in an armed holdup gone wrong, and the other son is in prison. So now this wonderful old man is trying to keep people from joining.

Rugby league is the national sport, and something we [Australians] introduced, and it’s probably the one thing that is keeping New Guinea from falling apart. I would go that far.

During the State of Origin, the three-day contest between New South Wales and Queensland, the whole country stops. Every three year old knows the top players in [Australia's] National Rugby League. It certainly influences young people to try to do something positive.

R&K: You shot these pictures in 2004. What has become of the subjects?

SD: A lot of them are no longer Raskols, a lot of them have jobs. A lot of them have actually grown up and moved on. Some have died, some are in prison. It’s important to have that as an up to date analysis of who these people are.

I went back to photograph them in 2011, and a lot of them didn’t want to be photographed. Mainly because they thought I was making money off of them. The reality of that is not true, of course. I was all self-funded, and there’s no money in books, and very little in magazines. But that’s very hard for them to understand. They see a book, and they think you’re making money.

–

Raskols by Stephen Dupont is published by powerHouse Books. Purchase here.

|

| A picture from Raskols |

The brain trust at the Economist Intelligence Unit regularly lists Port Moresby, the capital city of Papua New Guinea, as one of the world’s least liveable cities. Among their complaints: post-colonial malaise, poor schools, and, of course, lots of crime.

That’s where the Raskols come in. These urban gangsters are both the tormentors and occasional protectors of the settlements they live in. The settlements, little more than shantytowns, are divided along ethnic lines, and tribal conflict has been a way of Papua New Guinea life since long before the Australian colonists ever arrived. Raskols protect their own when violence strikes. But outside of those moments of need, they also steal, rape and murder.

The fact that Raskols and their curious uniform—handmade firearms, aviator shades and highlander talismans—have gained notoriety far outside of Papua New Guinea is largely due to the work of documentarians like Australian photographer Stephen Dupont. His book Raskols, full of searing portraits like the ones above, gives readers a glimpse into the personalities of these enforcers, but it also, in the eyes of some, glorifies a very real and very predatory subculture. Yesterday we caught up with Dupont, who has just arrived home in Australia after an assignment in Afghanistan, about Raskols, his critics, and why Port Moresby isn’t as bad as the Economist thinks.

Roads & Kingdoms: How was Kabul?

Stephen Dupont: Same same, but different. I guess they’re all gearing up to leave. There’s a vibe that people have had enough and just want to get out. Certainly with the Australians, who I was with.

R&K: You’ve mentioned in interviews that you don’t see Port Moresby as being as bad as cities like Kabul.

SD: Port Moresby gets an unneccesarily negative rap… Certainly when I first went there in 2004, it was pretty grim. But I’ve been in some cities in Africa that were far more dangerous and far more unliveable than Port Moresby. It’s improving. The fact that there’s a big mining boom has helped. They’ve got a big cinema and some shopping complexes coming up.

Yes, Raskols [are] still running around the city and doing what criminals do, robbing and raping and nasty things like that. But I think again, it’s not Kabul, it’s not Aleppo. It’s not what Grozny used to be, not Lagos, or even parts of Johannesburg or Zimbabwe. There are certainly parts of the world that I would feel more scared as a white person.

That’s also because I’ve been going there for a while. It’s still a city with razor wire, compounds, and people do tend to hide behind their gates. But embassies are running, business is running, expats are driving everywhere.

R&K: How many trips have you made out to Port Moresby?

SD: Probably about 12 trips. My 2011 fellowship [at Harvard's Peabody Museum] allowed me to spend a lot of time there working on my next book. It doesn’t look at Raskols so much. The underlying theme is to look at decolonization, how New Guinea is changing rapidly. I was really focusing on tribal traditions.

R&K: Are there aspects of a tribal culture to the Raskols? Or is it the same kind of gangsterism you’ll find anywhere else?

SD: It really is quite tribal. And territorial. The settlements are like ghettos. These gangs rise up to really act as a security force to protect the settlements in times of tribal conflict. But individuals will often go off on their own and commit crimes.

On the main roads at nighttime they’ll often try to jack cars, basically armed holdup stuff… particularly Friday and Saturday night when they’ve been around alcohol or drugs.

Their culture really comes through in the way they dress and behave. They have tribal colors. But you’ll see a little bit of western culture. Ice Cube and Bob Marley t-shirts with a traditional Billum bag [a lot will wear billums around their neck].

And something I don’t think you’ll see in another part of the world, is that they make their own guns. I think it’s quite strange, and beautiful, almost like art pieces… It sort of goes back to how they would make their weapons in tribal times.

R&K: What do you say to critics who say the work just “glorifies” gang culture?

SD: There’s always a risk in the representation of any gang or military culture where you’re showing people with weapons and so forth. But that aside, it’s more about: this is reality. This is how they are. My job as documentary photographer is to represent them as they are, not to glorify them. When I made the photograph, I didn’t set them up. I would go so far as to ask someone to stand in front of the camera, but then I would just wait, to capture something that revealed something.

Within their gang culture, they are vain, they are egotistical, they want to show off their guns. That’s just who they are. The only answer then would be to not show them, but that’s not who I am.

Sebastião Salgado gets criticized for romanticizing the poor, the refugees. It comes down to this: if you’re a photographer, you’ve got to present it in the most creative way possible… His photography is stunningly beautiful. He just chooses to photograph that subject matter.

It’s not Hollywood, we’re not doing a fashion show here. We’re trying to capture a side of society that just happens to be a dark side.

R&K: The Raskols are mostly young men of the same age as the troops you photographed in Afghanistan. Did you see any similarities in them as young men?

SD: Be it a gang in Port Moresby or a platoon in Afghanistan, there’s that sense of family, of camaraderie. Raskols stick together. And they definitely use a form of uniform. Certainly, though, soldiers are there to perform a job their government has endorsed. You can’t really compare soldiers to criminals.

R&K:How do the tribal elders feel about the presence of the Raskols?

SD: Generally speaking, the elders are against Raskol culture. I’m actually dealing right now with that kind of situation: I’m doing a documentary about a rugby league, and one of the coach’s sons was one of the Raskols I photographed.

The son was shot and killed in an armed holdup gone wrong, and the other son is in prison. So now this wonderful old man is trying to keep people from joining.

Rugby league is the national sport, and something we [Australians] introduced, and it’s probably the one thing that is keeping New Guinea from falling apart. I would go that far.

During the State of Origin, the three-day contest between New South Wales and Queensland, the whole country stops. Every three year old knows the top players in [Australia's] National Rugby League. It certainly influences young people to try to do something positive.

R&K: You shot these pictures in 2004. What has become of the subjects?

SD: A lot of them are no longer Raskols, a lot of them have jobs. A lot of them have actually grown up and moved on. Some have died, some are in prison. It’s important to have that as an up to date analysis of who these people are.

I went back to photograph them in 2011, and a lot of them didn’t want to be photographed. Mainly because they thought I was making money off of them. The reality of that is not true, of course. I was all self-funded, and there’s no money in books, and very little in magazines. But that’s very hard for them to understand. They see a book, and they think you’re making money.

–

Raskols by Stephen Dupont is published by powerHouse Books. Purchase here.