By SUSAN DONALDSON JAMES

By SUSAN DONALDSON JAMES Feb. 22, 2012

Benjamin "Benjy" Stacy so frightened maternity doctors with the color of his skin -- "as Blue as Lake Louise" -- that he was rushed just hours after his birth in 1975 to University of Kentucky Medical Center.

As a transfusion was being readied, the baby's grandmother suggested to doctors that he looked like the "blue Fugates of Troublesome Creek." Relatives described the boy's great-grandmother Luna Fugate as "blue all over," and "the bluest woman I ever saw."

Doctors don't see much of the rare blood disorder today, because mountain people have dispersed and the family gene pool is much more diverse.

But the Fugates' story still offers a window into a medical mystery that was solved through modern genetics and the sleuth-like energy of Dr. Madison Cawein III, a hematologist at the University of Kentucky's Lexington Medical Clinic.

Cawein died in 1985, but his family charts and blood samples led to a sharper understanding of the recessive diseases that only surface if both parents carry a defective gene.

The most detailed account, "Blue People of Troublesome Creek," was published in 1982 by the University of Indiana's Cathy Trost, who described Benjy's skin as "almost purple."

The Fugate progeny had a genetic condition called methemoglobinemia, which was passed down through a recessive gene and blossomed through intermarriage.

"It's a fascinating story," said Dr. Ayalew Tefferi, a hematologist from Minnesota's Mayo Clinic. "It also exemplifies the intersection between disease and society, and the danger of misinformation and stigmatization."

Methemoglobinemia is a blood disorder in which an abnormal amount of methemoglobin -- a form of hemoglobin -- is produced, according to the National Institutes for Health. Hemoglobin is responsible for distributing oxygen to the body and without oxygen, the heart, brain and muscles can die.

In methemoglobinemia, the hemoglobin is unable to carry oxygen and it also makes it difficult for unaffected hemoglobin to release oxygen effectively to body tissues. Patients' lips are purple, the skin looks blue and the blood is "chocolate colored" because it is not oxygenated, according to Tefferi.

"You almost never see a patient with it today," he said. "It's a disease that one learns about in medical school and it is infrequent enough to be on every exam in hematology."

The disorder can be inherited, as was the case with the Fugate family, or caused by exposure to certain drugs and chemicals such as anesthetic drugs like benzocaine and xylocaine. The carcinogen benzene and nitrites used as meat additives can also be culprits, as well as certain antibiotics, including dapsone and chloroquine.

The genetic form of methemoglobinemia is caused by one of several genetic defects, according to Tefferi. The Fugates probably had a deficiency in the enzyme called cytochrome-b5 methemoglobin reductase, which is responsible for recessive congenital methemoglobinemia.

Normally, people have less than about 1 percent of methemoglobin, a type of hemoglobin that is altered by being oxidized so is useless in carrying oxygen in the blood. When those levels rise to greater than 20 percent, heart abnormalities and seizures and even death can occur.

But at levels of between 10 and 20 percent a person can develop blue skin without any other symptoms. Most of blue Fugates never suffered any health effects and lived into their 80s and 90s.

"If you are between 1 percent and 10 percent, no one knows you have an abnormal level and this might be the case in a lot of unsuspecting patients," he said.

Many other recessive gene diseases, such as sickle cell anemia, Tay Sachs and cystic fibrosis can be lethal, he said.

"If I carry a bad recessive gene with a rare abnormality and married, the child probably wouldn't be sick, because it's very rare to meet another person with the [same] bad gene and the most frequent cause therefore is in-breeding," Tefferi said.

Such was the case with the Fugates.

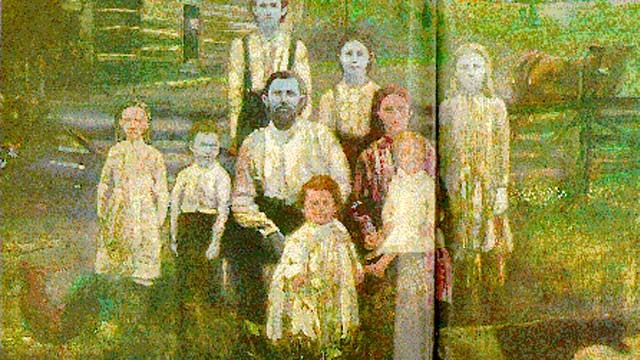

Martin Fugate came to Troublesome Creek from France in 1820 and family folklore says he was blue. He married Elizabeth Smith, who also carried the recessive gene. Of their seven children, four were reported to be blue.

There were no railroads and few roads outside the region, so the community remained small and isolated. The Fugates married other Fugate cousins and families who lived nearby, with names like Combs, Smith, Ritchie and Stacy.

Benjy's father, Alva Stacy showed Trost his family tree and remarked, "If you'll notice -- I'm kin to myself," according to Trost.

One of Martin and Elizabeth Fugate's blue boys, Zachariah, married his mother's sister. One of their sons, Levy, married a Ritchie girl and had eight children, one of them Luna. Luna married John E. Stacy and they had 13 children.

Benjy descended from the Stacy line.

ABCNews.com was unable to determine if Benjamin Stacy is still alive -- he would be 37 today. Trost writes that he eventually lost the blue tint to his skin, but as a child his lips and fingernails still got blue when he was angry or cold.

His mother Hilda Stacy, who is 56, appears to still live in Hazard, Ky., but did not answer calls to her home. Other relatives are scattered throughout Virginia and Arkansas.

Most of what scientists know about the family was discovered by Cawein, the grandson of Kentucky's poet laureate, who had done pioneering research on L-dopa as a treatment for Parkinson's disease.

Later in 1965 he was famous for another reason. His wife was murdered by chemical poisoning, but no one was ever indicted.

Cawein heard rumors about the Fugates while working at his Lexington clinic and set off "tromping around the hills looking for blue people," according to Trost's account.

At an American Heart Association clinic in the town of Hazard, Cawein found a nurse, Ruth Pendergrass, and she was willing to assist. She remembered a dark blue woman who had come to the county health department on a frigid afternoon seeking a blood test.

"Her face and her fingernails were almost indigo blue," she told Trost. "It like scared me to death. She looked like she was having a heart attack. I just knew that patient was going to die right there in the health department, but she wasn't a'tall alarmed. She told me that her family was the blue Combses who lived up on Ball Creek. She was a sister to one of the Fugate women."

More families were found -- Luke Combs, and Patrick and Rachel Ritchie, who were "bluer'n hell" and embarrassed by their skin color.

Cawein and Pendergrass began to ask questions -- "Do you have any relatives who are blue?" -- and mapped a family tree and took blood samples.

The doctor suspected methemoglobinemia and uncovered a 1960 report in the Journal of Clinical Investigation. Dr. E. M. Scott, who worked in public health at the Arctic Research Center in Anchorage, had seen a recessive genetic trait among Alaskans that turned their skin blue.

That suggested an inbred line that had been passed from generation to generation. To get the disorder, a person would have to inherit two genes -- one from each parent. When both parents have the trait, their children have a 25 percent chance of getting the disorder.

Scott speculated these people lacked the enzyme diaphorase in their red blood cells. Normally diaphorase converts methemoglobin back to hemoglobin.

All of the blue Fugates he tested had the enzyme deficiency, just like the Alaskans Scott had observed.

Their blood had accumulated so much of the blue molecule that it over-powered the red hemoglobin that normally turns skin pink in most Caucasians.

The bluest of the bunch was Luna, and she lived a healthy life, bearing 13 children before she died at the age of 84.

As coal mining arrived in Kentucky in 1912 and the Fugates moved outside of Troublesome Creek, the blue people began to disappear.

Doctors say Benjy likely carried only one gene for methemoglobinemia, because he eventually had normal skin tones, and the likelihood of him marrying a woman with the same recessive gene would have been small.

By the time reports appeared in the media on the disorder, the Stacy family was upset with insinuations about in-breeding that fed into stereotypes of backwoods Appalachia.

"There was a pain not seen in lab tests," wrote Trost. "That was the pain of being blue in a world that is mostly shades of white to black."

http://abcnews.go.com/Health/blue-skinned-people-kentucky-reveal-todays-genetic-lesson/story?id=15759819